Test First - Part 3

On the Relevance of the Classical Testing Pyramid

Looking at an Ancient Structure

TL;DR #

The classical testing pyramid focuses on the cost of writing, running, and maintaining tests, which is a narrow and single-minded perspective not adapted to today’s technology landscape.

In the second part of this series, I stress the importance of focusing on testing actual requirements, behavior, use-cases, and not implementation details like methods and classes.

Yet things aren’t merely as simple as that. Through shedding new light on the classical testing pyramid, this article will challenge long-held testing dogmas, advocating for a paradigm shift that better aligns with the complexities and nuances of contemporary software ecosystems

A short history lesson #

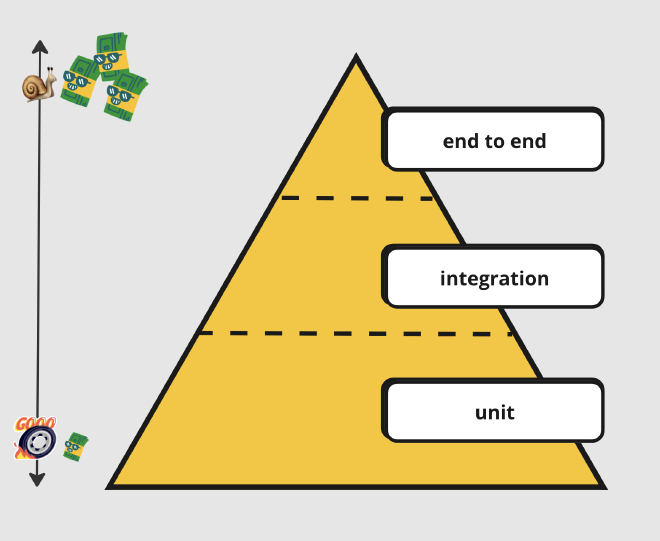

Most developers are familiar with the concept of the testing pyramid, introduced by Mike Cohn in his book “Succeeding with Agile: Software Development Using Scrum” back in 2009. It suggests an ideal test distribution:

- A solid base of unit tests

- A middle layer of integration tests

- A smaller top layer of end-to-end tests

The pyramid emphasizes a particular aspect of test type distribution,

primarily based on the cost — in terms of time and money —

associated with writing, running, and maintaining tests.

However, it solely considers this aspect of cost distribution,

overlooking other valuable factors that should also be taken into account.

Unit Tests are a Weak Foundation #

In today’s software development world, the testing pyramid’s foundation isn’t as sturdy as it once was. It’s built on the idea that having many unit tests equals a well-tested application, but this can be highly misleading. As we discussed before, the ambiguous nature of unit testing in our industry typically guides us to write numerous isolated tests, all while mocking out external dependencies. This practice eventually leads to a brittle test codebase.The focus on technical distribution steers us away from the real goal of testing behavior.

In essence, the classical testing pyramid tells us how to test things, but it’s not all that relevant because it doesn’t help us:

- prevent regression

- document our software

- refactor freely

- and evolve our applications at a steady pace, all of that when making changes without altering requirements

Honeycomb to the rescue #

With the exponential growth of the web came the need for microservices, the evolution of architectural patterns, new types of databases, queues, and the ever-increasing speed and power of our computers. We are no longer creating the same applications as we did in the past. I argue that these shifts have undoubtedly influenced the way we write tests.

Over the past decade, there has been a noticeable shift towards a multitude of leaner services, moving away from monolithic applications. These modern services are often simplified, with a reduced business responsibility, while the emphasis has shifted towards integration with other services and infrastructural components.

Advancements in CPU cycles and virtualization have propelled us into an era where entire databases can be spun up in a matter of seconds when running tests, thanks to tools like Testcontainers.

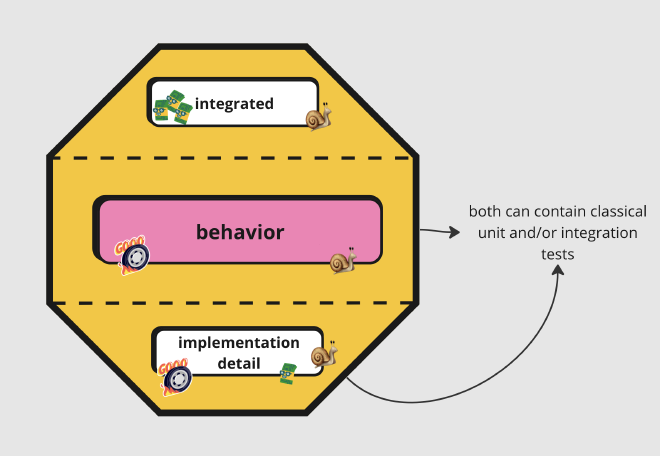

As a response to these changes, the testing honeycomb model has emerged, placing greater emphasis on integration tests and placing less focus on implementation details and integrated tests.

A Honeycomb++ #

From today’s perspective, I recognize increased value in the testing honeycomb,

positioning integration tests as the cornerstone of a modern testing approach.

I would like to propose a minor adjustment,

shifting focus from the type of test to the true value of testing –

in other words, emphasizing the importance of testing behavior.

Spotlight On Behavior Testing #

At its core, you test the behavior of your system through various means such as unit, integration, slice, component, or any other type of test required.

👉 A behavior test says nothing about the type of test, being unit or integration. This choice, or rather architectural decision, is yours to take and varies for each context.

Implementation detail #

It is important to state that testing implementation details, even on a class or method level, is not wrong and at times even necessary, especially for complex logic within a component.

👉 However, it should never, like the classical testing pyramid implicitly proposes, be the foundation of your test distribution.

To admit, it’s not always clear what actually is an implementation detail test. This is something that should be formulated for every project and is part of the architecture of your application.

Testing implementation details means focusing on the specific, internal workings of a piece of software, such as the methods, classes, and internal state and flow, rather than on its overall behavior or the outcomes it produces.

Internal Focus: These tests concentrate on the internal structure of the code, rather than on what the code does from a behavioral perspective.

Susceptibility to Change: Tests that focus on implementation details are often fragile and prone to failure with code refactoring or internal changes, even when the external behavior remains consistent.

State Verification: They frequently involve verifying the internal state of an object or the interactions between internal components, rather than the end result or output of a process.

It is easy to fall into the trap of over-testing simple orchestration code. This occurs when tests are written for code that merely coordinates or orchestrates calls to other components. For instance, testing an isolated Spring MVC controller or service might seem beneficial, but if these tests only assess how the code is structured internally, rather than how it behaves or interacts with other layers within the system, they may be focusing too much on implementation details.

Integrated #

These tests are conducted in actual environments to identify integration failures, and that can even be in production. Often, our system landscape includes a variety of microservices, databases, queues, and other infrastructure components. These are orchestrated by a complex mix of release and deployment pipelines, comprising scripts, infrastructure-as-code definitions, and configuration files. Collectively, they form a functioning end-to-end system.

An integrated test examines the entire landscape in an actual environment, akin to a smoke test.

To offer a more concrete example: in a recent project, I worked with Kafka, where AVRO messages were published. This process required a pre-existing schema in a component known as the schema-registry. Frequently, someone would forget to add or update the schema in our Terraform repository.

All tests locally were succeeding, and even upon deployment to the dev environment, everything seemed up and running. Until our automated test fired some calls against the system that caused it to fail because of the missing schema. This could indeed have been captured by a manual test, yet there is great value in automating things.

What does an integrated test it look like? #

It can be as simple as a set of shell or python scripts firing off some requests against the system and waiting for a certain response. Something that can be run after each deployment in an environment.

Mapping the cost and duration on the Honeycomb #

When we map the cost and duration of tests onto the honeycomb model, a more balanced distribution emerges. With the behavior tests being the most balanced as they can be both slow and fast at the same time. There is a cost to implementation detail tests, as they are susceptible to break upon refactoring. Integrated tests, on the other hand, represent the highest expense in both execution and maintenance, due to their complex nature and the ongoing challenge of upkeep.

👉 In essence, when all behavior is thoroughly tested, it often results in most of the code being effectively covered.